Last year, the ballot boxes opened across six Southern African countries—Mozambique, Namibia, Madagascar, Mauritius, and Botswana—to test the strength of their democratic institutions. These elections didn’t just reshuffle parliaments—they tested the seams of what holds, and what’s coming apart across the Southern African region.

Taking these lessons forward, the second Southern Africa Election Academy—hosted by the Electoral Support Network for Southern Africa (ESN-SA) from 24 to 25 April 2025—offered a neutral, inclusive space for election officials, policymakers, civil society, academics, and observers to collaboratively shape practical recommendations ahead of the 2025 elections in Malawi, Seychelles, and Tanzania.

Ballots and balances

South Africa’s recent transition to multiparty coalition governance, Namibia’s historic election of a female President and the creation of a gender-balanced Cabinet, and the peaceful transfer of power following Botswana’s elections were all responded with great recognition during the academy.

However, not all was cause for celebration. Southern Africa’s elections also exposed systemic challenges: inadequate voter education, electoral material shortage, diaspora voting barriers, pervasive influence of social media and the proliferation of information disorders, electoral violence, the “over-judicialisation” of elections — a high number of court cases to resolve election-related issues taking place close to the election day itself, which can delay the process and disrupt practical planning and organisation — low participation rates among youth and marginalised groups and a trust deficit.

Trust, trust, trust…

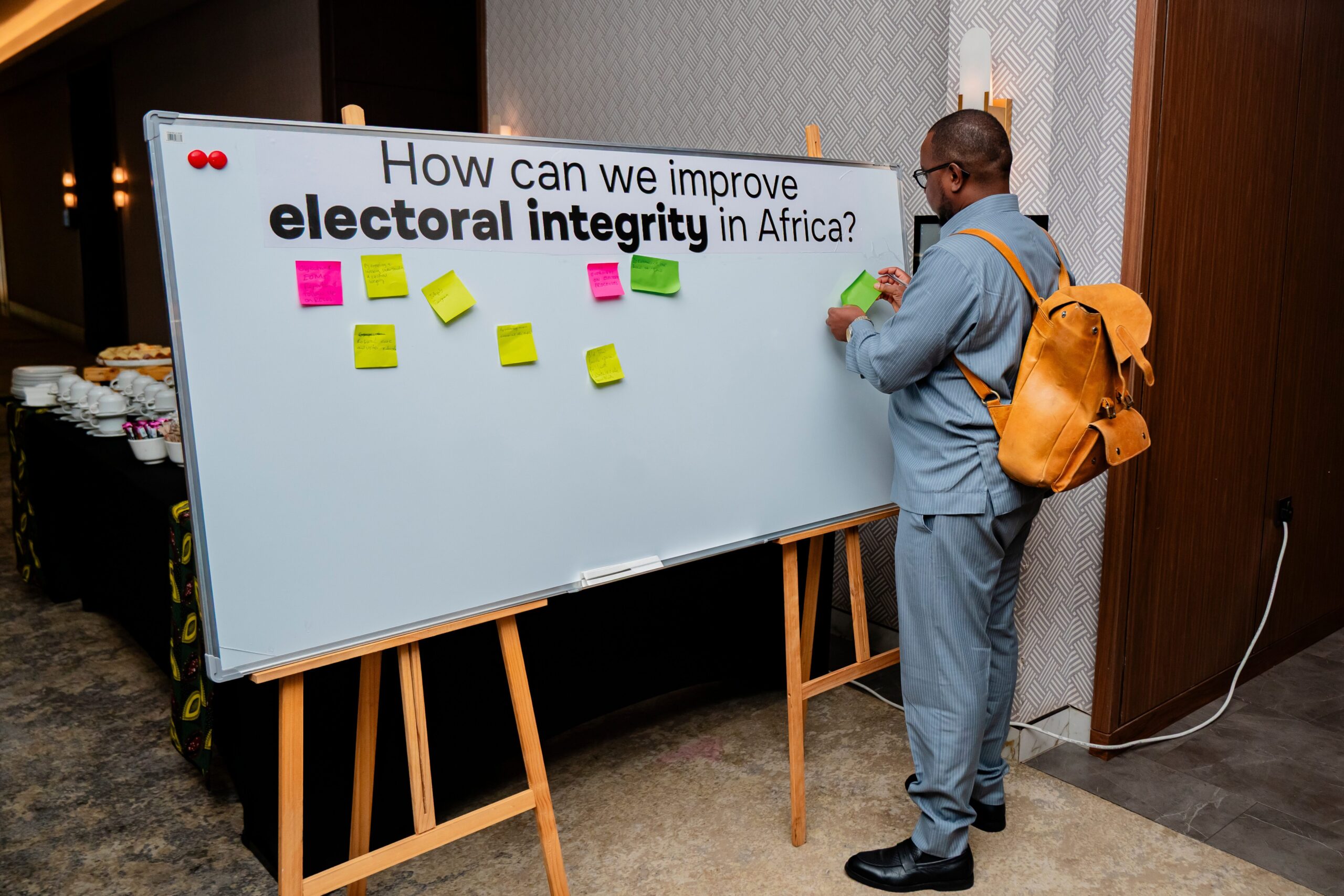

This isn’t a Megadeth song, but the word ‘Trust’ echoed louder in the Radisson Hotel—where the academy took place—than at any of their concerts, you can be sure of it.

Trust deficit became the defining feature of the electoral climate across Southern Africa, as speaker after speaker pointed to it as a major concern. The consequences extend well beyond voter apathy, showing a strong correlation with the concerning trend of declining voter turnout, as noted by Simelane Nkanyiso, representative of the European Union Delegation in South Africa. In fact, Professor Everisto Benyera from the University of South Africa went even further, predicting that voter turnout in South Africa could drop from 37% to just 10% within the next 15 years if current patterns persist, while Professor Khabele Maltosa, author of the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (ACDEG), emphasised the need to significantly increase investment directed towards bolstering electoral integrity in order to address voter participation concerns.

New horizons

The way out of the prospect of such a democratic deficit could be a (1) a shift towards a developmental democracy that addresses core survival issues and reflects citizens’ socio-economic needs, as highlighted by Professor Khabele Matlosa; (2) leveraging the public’s trust in religious leaders; and (3) reaffirming to the following six broad commitments, as highlighted by National Democratic Institute Director of Elections Richard Klein:

- Genuine elections that reflect the will of the people

- Election rights and responsibilities free from discrimination

- Professional and impartial election administration

- Timely, transparent resolution of complaints and disputes

- Non-discriminatory access to media

- International cooperation to advance democratic norms and credible elections

These commitments aim to address what Felix Kafuuma, Programmes Manager at the African Election Observers Network (AfEONet), harshly described as the ‘four cancer cells’ of electoral integrity: money, manipulation, institutional weakness, and intimidation and violence. The Southern African 2024 Elections Compendium of Recommendations strongly embraces these six commitments and was officially launched during the Election Academy. The recommendations put forward are context-specific – it was accentuated during the academy that equality in election results amongst countries does not necessarily reflect equality in their post-election conditions – and were formed based on the findings from ESN-SA’s 2024 Election Observation Missions in South Africa, Mozambique, Botswana and Namibia supported by AHEAD Africa.

Drawing on their frontline experience, ESN-SA also presented an Election Observation Manual during the academy to guide domestic observers in their work. The manual is designed to help ensure the integrity of the electoral process, promote observer safety and ethical conduct, enhance methodological consistency, strengthen reporting and documentation, and improve observers’ response to incidents. However, as Samson Itodo from Yiaga Africa pointed out, perhaps future conversations may need to focus on rethinking election observation methods, moving beyond ritualistic practices and perhaps even shifting from traditional monitoring to movement building?

Pictures on the Southern Africa Election Academy II